Google Lens promises to make your phone’s camera smarter. When Google CEO Sundar Pichai introduced Google Lens in May 2017, he suggested that it could recognize a flower, find restaurant ratings, or quickly connect your phone to WiFi. Other presenters suggested that Google Lens could capture business card contact data, identify books and music, or extract an address– all from an image.

Google Lens works with Google’s own Pixel line of smartphones, as of January 2018. If you own one, you can experiment with Google Lens in either Google Photos or Google Assistant.

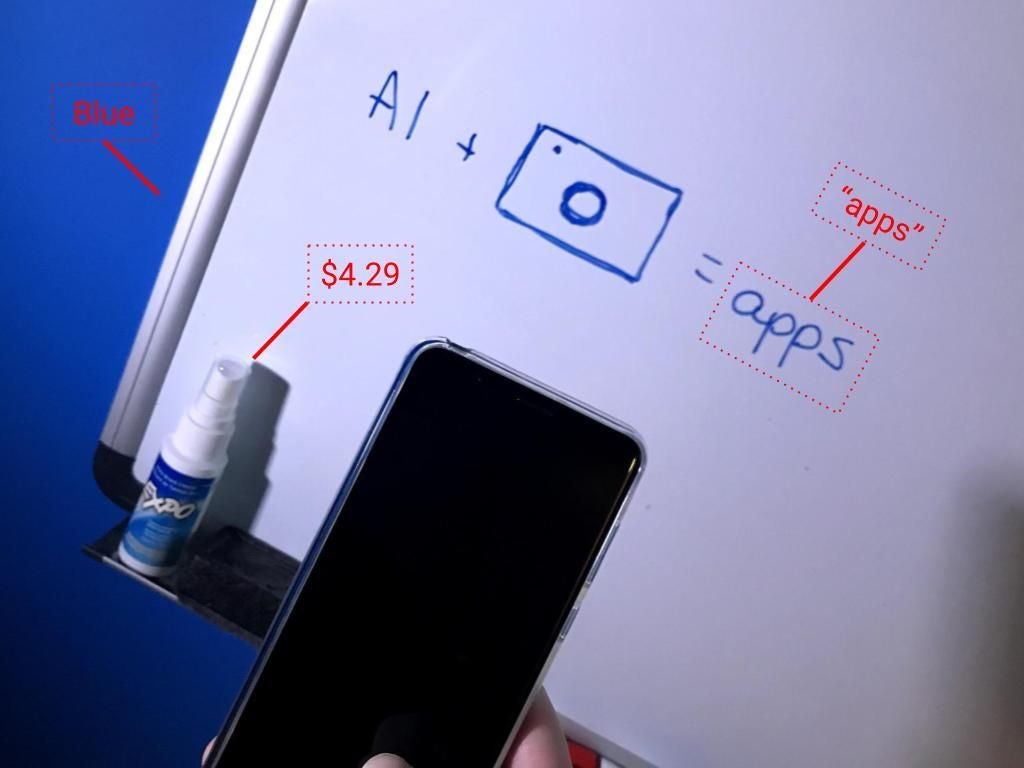

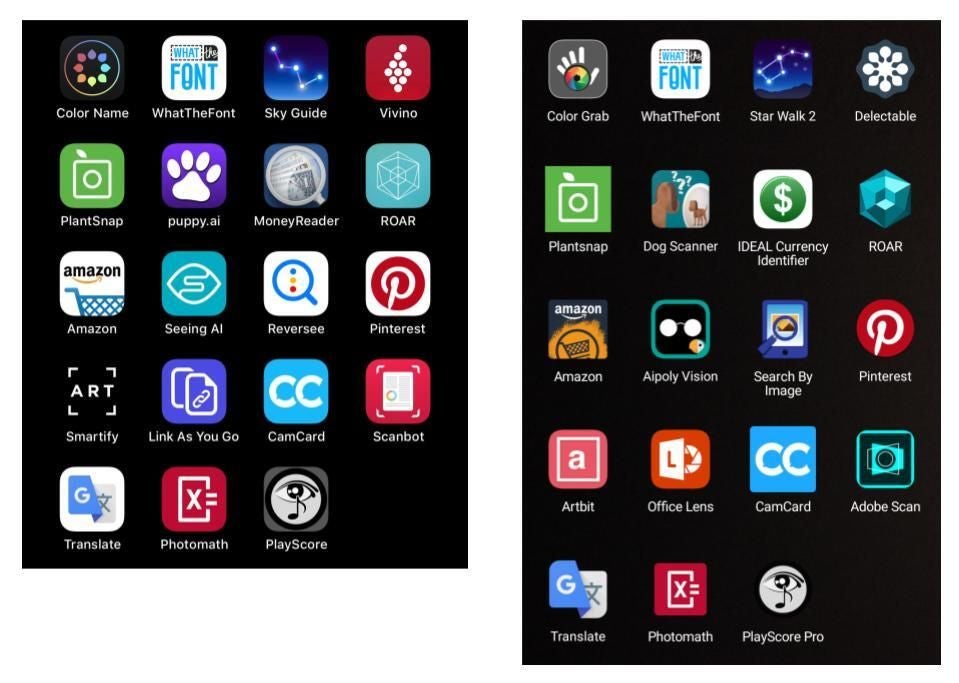

Many of the features Google Lens delivers already exist, but they’re tucked inside individual apps. For example, you can install apps on an iPhone or Android device today that use the camera to:

- Identify colors (Color Name, Color Grab)

- Identify fonts (What The Font)

- Identify stars (Sky Guide AR, Star Walk 2)

- Identify wine (Vivino and Delectable)

- Identify plants (PlantSnap)

- Identify dogs (Puppy.ai, Dog Scanner)

- Identify money (MoneyReader, IDEAL Currency Identifier)

- Find consumer packaged good information (ROAR)

- Find products (Amazon)

- Read text, identify objects, food, products, and more (Microsoft’s Seeing AI, Aipoly Vision)

- Search for similar images (Reversee, Search By Image)

- Search for similar items (Pinterest)

- Provide information about art in some locations (Smartify, Artbit, Google Arts & Culture)

- Extract links (Link As You Go, Office Lens)

- Capture contact information from a business card (CamCard)

- Scan and turn documents into editable text (Scanbot, Adobe Scan)

- Translate text (Google Translate)

- Solve a math problem (PhotoMath)

- Convert printed music into editable or playable notes (PlayScore Pro, NotateMe’s PhotoScore)

To use each feature you first have to install an app. Then tap the app, point the phone, and capture the image every time you want to use the camera for that task. An app that extracts business card contact information doesn’t identify wines, recognize dogs, or solve math problems. A music recognition app rejects a photo of a dog as unplayable. (Yes, I tried it.) The software looks for particular patterns to identify and match. Each app performs a narrow task.

The promise of Google Lens is that we can point-and-talk (or point-and-type). It’s easy to envision a future where you pick up your device, point it at something, say “Hey Google, what is this font?” then see or hear a response. Your request, whether spoken or typed, essentially serves as an app-switcher. Is the system supposed to find fonts? Extract a phone number? Identify colors? Your words help narrow the field of potential results.

Google Lens may have significant implications for developers and companies. Developers of smart camera-reliant apps need to make sure to create value beyond object or element recognition. I anticipate that developers and companies will build apps that integrate image recognition tasks into workflows: pick up your phone, point-and-talk to recognize a product, change a status in a system, and push a notification to a colleague.

In some sense, the advent of Google Lens reminds me of the early days of computer graphic design. Initially, every design change or image manipulation required a separate programmed routine or application. Later, we built more powerful tools that let us use one tool for multiple functions. Today, we’re in much the same place with our smartphone cameras: We need dedicated apps. Google Lens could reduce our need for apps as it adds artificial intelligent camera features.

What do you see?

What other apps have you used that rely on your smartphone’s camera and machine learning systems? If you’ve used Google Lens, what are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments below or or Twitter (@awolber).