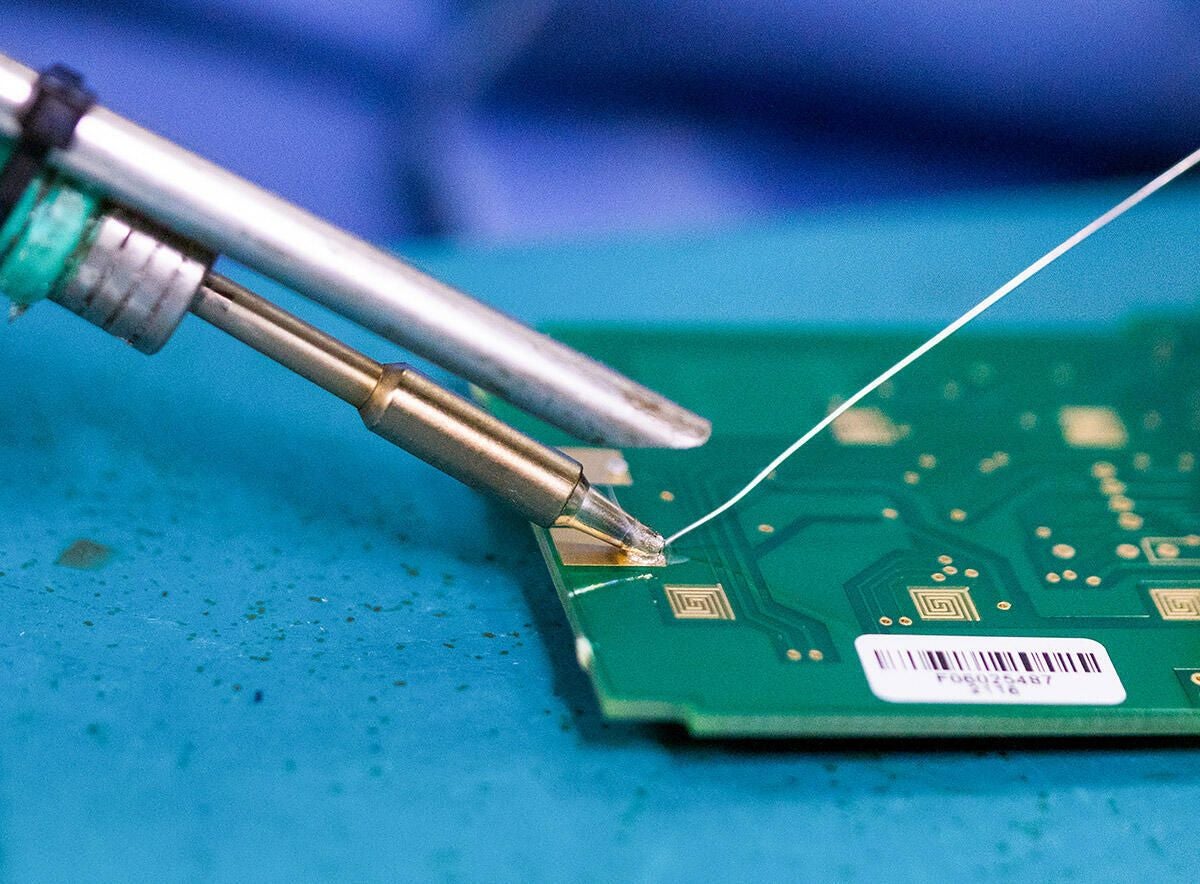

Image: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Manufacturing is making a comeback in most industries after languishing during the pandemic and supplies of chips—used to operate most devices—are in short supply. The shortage is being felt acutely in the automotive industry and will for as long as two years, analysts say.

One of the issues is there isn’t the return on investment to build foundries to satisfy the demand by the automakers, said Mario Morales, program vice president of the semiconductor group at IDC. Many are also not investing in “what we’d call legacy technology,” Morales said.

SEE: Global chip shortage: The logjam is holding up more than laptops and cars and could spoil the holidays (TechRepublic)

Poor planning is one cause of global chip shortage

Another problem is poor planning. During the second quarter of 2020 automotive OEMs “shut down, as did most of the world, but as they did that they canceled orders from a lot of the supply chain,” Morales said. “So a lot of disgruntled suppliers found other markets that were still doing well despite the pandemic.”

These include the big eight cloud infrastructure providers, which saw demand skyrocket when people began working from home and children were attending school remotely, causing a massive spike in PCs, tablets and consumer electronics, he said.

Trade sanctions and phone rollouts added to global chip shortage

Earlier this month, Gartner analysts said they expect the worldwide semiconductor shortage to last until the second quarter of 2022.

Add to this rollout of the 5G smartphone and the trade sanctions the U.S. placed on China before the pandemic, said Gaurav Gupta, a vice president analyst at Gartner. This meant Huawei, one of the largest 5G smartphone makers in China, couldn’t buy chips after a certain time, Gupta said. “They knew they couldn’t procure chips for their products … so they placed big orders.”

Likewise, Apple and other smartphone makers also placed large chip orders, “which kept the foundries extremely busy, then you had the sudden increase in demand for COVID-19,” Gupta said.

The role of the pandemic in the global chip shortage

The pandemic played a big role, said Glenn O’Donnell, vice president research director at Forrester, in a recent blog post.

“Demand for cloud computing services from providers like AWS, Microsoft Azure and Alibaba continues to skyrocket. They buy lots of semiconductors,” O’Donnell wrote.

“Mobile phone sales remain hot. Makers like Apple, Samsung, and Huawei buy lots of chips. PCs are hot … Piled atop all that is a shortage of GPUs and other chips gobbled up by cryptocurrency gluttons. Demand is hotter than ever, and it’s only getting hotter.”

The global shortage is cutting a wide swath beyond mobile devices. “If it has a plug or a battery, it is probably full of chips,” O’Donnell wrote.

Gupta said, “The wireless community, industrial, aerospace, military—anyone or everyone whose products require semiconductor chips is facing a shortage.”

A few isolated events, including an earthquake and semiconductor fabrication plant fire in Japan and a winter storm in Texas in March, which shut down some fabs this year, have also contributed to the problem, Gupta said.

Automotive, industrial sectors suffering most due to global chip shortage

Morales said the automotive and industrial market segments, which are still using legacy node technologies “are not only at the back of the line and don’t get priority [for chip orders] like smartphones, PC or cloud infrastructure [providers] would get … it’ll take longer for them to recover.”

These industries have inefficient supply chains, and even if they could get chips to move upstream, it could take months for them to reach the end product, he said.

“They might get the chips by the third quarter of this year [then] they’ll finally start seeing production but it will not be until the first half of next year potentially, that you will see cars with chips that they were asking for to run intelligent smart systems, ABS brakes or powertrain,” Morales said.

Besides the fact that they use legacy technologies, these industries are also a low priority because when they shut down last year they forced the semiconductors “to take on the risk of uncertainty. So a lot of suppliers moved to other products and they’ll move to the automotive industry when they’re ready.”

In contrast, gaming companies have experienced “a tightness in supply,” because they are more on the leading edge side and forecasted products better, Morales said.

“A lot of this has to do with the business decisions [companies] made. Automotive operates in a just-in-time environment,” he said. “When you’re shocked by the pandemic it’s hard to operate without business continuity planning.”

The Japanese semiconductors and automotive companies “aren’t crying shock” because they know what to expect from past tsunamis and earthquakes, and are able to better anticipate their supply needs, Morales said.

There is no short-term solution, according to Gupta. “If supply is constrained you can’t increase it in a short timeframe …. We’re looking at the second quarter of next year” before lead times improve. In the meantime, prices will go up.

This article was updated on May 28, 2021.